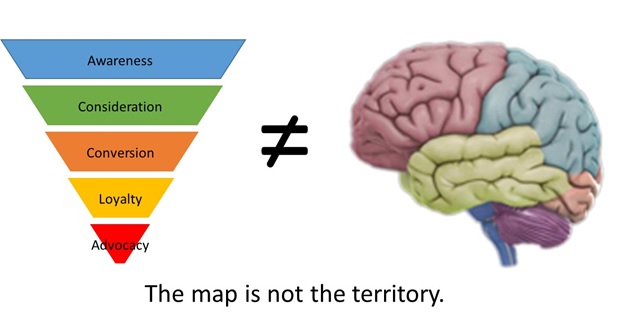

Don’t Confuse Your Funnel With Reality

May 28, 2014 Industry News, Marketing, Marketing And Advertising Analytics, Optimization, Search Analytics, Web Analytics

Models are supposed to make it easier to see useful patterns, but if you devote enough time to using them you can forget you are looking at a simplified view of reality and not reality itself. The marketing funnel is a great example of how this can happen.

When you are trying get a holistic view of your marketing plan, it is often helpful to segment the audience according to where they are on the path from never having heard of your brand to the end state of buying your product. It can make things clearer. Let’s say you have done some analysis of the buying process for your product and you have found that people move through it like this:

Let’s further say your numbers say that the conversion rates for a given month look like this:

The numbers indicate that once someone is researching your product you have a really good chance of making them a customer. Depending on your cost per acquisition and the value of your product, you’d probably want to step up your efforts to drive them to your site.

Would that still be your conclusion if you knew that:

The list of complicating factors could go on and on. The point is, you are looking at a model. Don’t forget there is a particularly complicated reality behind any marketing model: the mind of the buyer.

The Future of SEO: Not Provided

Sep 30, 2013 Industry News, Optimization, Search Analytics, Web Analytics

So, let’s see if I have mapped out this ecosystem correctly.

1. People come to Google.com to do searches, because they perceive that Google’s search results are the best.

2. SEM marketers bid on impressions of certain words and phrases relating to their product, and the winners’ ads show up at the top of the page before the natural (unpaid) results. Some more paid ads appear on the right-hand side of the page.

3. Part of each paid ad’s success in the auction for impressions has to do with how well the content on the landing page for the ad’s link corresponds to the terms the person was searching for.

4. The unbiased “natural” search results appearing after the paid ads also have a kind of competition going on behind them. A search algorithm has to decide which order to present them in, and does so based on a large number of factors.

5. Firms in the SEO space have built a business out of using an understanding of natural search result ranking algorithms to help redesign sites to be as discoverable as possible through natural search.

SEO is based, in large measure, on data about who arrives on which pages after searching for various terms – this group could be analyzed, segmented and treated differently based on what they expressed an interest in via search. Remove the information about which terms an individual is searching for, and you are now stuck analyzing natural traffic as a giant undifferentiated blob of traffic.

Google just rendered this data invisible for natural search clicks. Who does that benefit?

1. Google likes SEM, because that is where their paychecks come from.

2. SEM and SEO are interrelated. If your site is employing good SEO practices, your SEM is more efficient. That means you make more money and probably allocate more over time to SEM. This is good for Google, but in an indirect way.

3. SEO is harder without granular keyword data that can be used to tailor site content to user needs (or advertiser goals). This is not good for SEO providers.

4. If sites in general begin to be less searchable as a result of Google’s cessation of critical SEO data, then users’ experience of search could possibly decline. I guess that depends on whether you believe the activities are, taken in the aggregate, improving search results or degrading them. SEO improves the search experience to the extent that it tries to discern the searcher’s intent and deliver what they are looking for. SEO degrades the search experience if it is trying to trick a user into visiting a page that is not what they are searching for.

– Apparently Google either believes:

a. SEO hurts the experience more than it improves it, or

b. Some degradation in the user experience is OK in the service of making more money while being able to claim a privacy/security benefit.

In any case, the deed is done.

Perhaps the folks at Google is looking to take the business of SEO for themselves? I mean no one knows the rules better than the people who make up the rules, right?

Tags: encrypted search, Google

Optimization vs. Improvement

May 7, 2013 Industry News, Marketing And Advertising Analytics, Optimization, Statistics

The word “optimization” can be used to refer to a mathematical technique for selecting the best combination of controllable factors to maximize the value of an outcome or dependent variable. It can also be a fancy substitute for the word “improvement”, used to project the impression you are applying some kind of mathematical rigor, when in fact you are not.

This entire post may sound like nitpicking, but there is a real issue at stake.

The main difference is this:

– If you are collecting data to map out the entire feasible space of options, then picking the best solution, you are doing “optimization”.

– If you are trying two or three of something, and then picking the winner, you are doing “improvement by trial and error”.

“Optimization” leaves you with some assurance that you have left no improvement on the table. “Improvement by trial and error” may deliver value, but without a sense of whether there are further gains available.

In the realm of marketing analysis, this distinction is further tangled by the fact that there is no way to actually map out all possible creative executions, all the possible ways to deliver them to an audience (unless you believe all the good ideas have been done already, in which case you need historians and not creatives.)

So, when someone sells you creative optimization using a multivariate testing engine that automatically spits out thousands of combinations of a background image, a headline, a call to action and a button to click, you may think you are doing real optimization, but that is true only if your collection of copy bits and graphic elements represents the whole feasible range of creative executions and not just what someone could crank out in a week or so. That, IMHO, is not likely. It is really precision masquerading as accuracy or – put differently – marketers opting for the easily quantifiable to the exclusion of the extremely effective.

Not all marketing problems are best approached via formal optimization – particularly those where creative execution is a critical variable. But it is possible to apply good test design and measurement to understand when something works better than what we are currently doing and when it does not. Just don’t call that “optimization” – that is almost like lying.

How Not To Do An A/B Test

Oct 12, 2012 Industry News, Marketing And Advertising Analytics, Optimization, Search Analytics, Statistics, Web Analytics

There are a large number of ways to make a hot mess out of an A/B test. Here are five:

1. Don’t Measure Conversions

“We don’t have time to set up conversion tracking. Let’s just decide based on click rate.”

This is a terrible idea. Clicking and converting are two very different things, and click rates are often not correlated with conversion rates. For example, I click on pictures of Ferraris, because I like to look at Ferraris, but you can ask all my friends – I have never bought a Ferrari. I have bought a Mazda, a Toyota, a Datsun and a Ford Maverick. You can show me a Ferrari if all you want is clicks, but show me something I might actually buy if you want conversions.

2. Don’t Do Any Test Size Calculations

Ten minutes of work could tell you that you won’t have enough data to read your test even if you ran it for two years. Are you sure you can’t afford some time to do a Google search for “A/B Test Calculator” and plug some numbers into a form?

I’ll save you even more time, use this one: ABBA

3. Stick With Your Test Size Calculations No Matter What Happens

The test size calculations you did were based on some assumptions: confidence level, the magnitude of the difference you wanted to be able to detect, and the expected performance of the baseline or control. After you’ve run the test for a while you can begin to see where reality and your assumptions have parted ways. What should you do? Most people do repeated significance calculations and quit when they are satisfied with the significance. If you do this, you’ve spent too much time and opportunity cost on your test. You could have quit sooner, had you known about Anscombe’s Stopping Rule, which uses an approach called regret minimization, and you would actually end up with more conversions.

Check it out: A Bayesian Approach to A/B Testing

4. Don’t Think About Gating

What is gating?

Let’s say you have two different versions of a page: Version A and Version B. Let’s say your plan is to rotate them randomly. Let’s say your site and your content are such that most people come to the site repeatedly, say two to six times per week. If you are rotating Version A and Version B completely at random, then most of your users are going to see a blended treatment. This will reduce the effects of your test. To fix this, you want to make the version a person sees “sticky’ so one group sees only Version A during the test and the other group sees only Version B. That way each group sees a consistent treatment and you will see more of an effect (assuming the differences between A and B are substantial enough).

This is called “gating” and is done by randomly assigning new visitors (people with no gating in their cookie) to Version A or B, and then storing that in their cookie so that the next time they will see the same version.

5. Conclude That Your A/B Testing Result is Actually Optimal

An A/B test picks one “best” version for everyone. But isn’t it possible that there are some people in the audience who’d respond best to Version A and others who’d respond best to Version B? For that, you’d need to be able to collect lots of data about what kinds of users respond to the different options, and then you’d need a way to target the two versions at the audiences they work best with. Fortunately such tools exist.

Check out the toolset I work with every day at [X+1]: [X+1] Home Page

Conversion Optimization: It’s All About Action

Mar 21, 2010 Optimization, Statistics, Web Analytics

Optimizing your website to maximize the number of page views or visitors, while sounding reasonable, may unwittingly have you wasting marketing dollars and effort on people who won’t buy anything or participate on your website (or your advertisers’ websites) in the foreseeable future.

When you spend time and money on your site content or on audience development for your site, you want to make sure you are measuring the impact of those changes in terms of number of desired actions taken by visitors to your site, in terms of the efficiency with which you are spending resource. The key measure you are tracking on the cost side is the ECPA, or effective cost per action. If you have a small site and are passive about audience development, perhaps it makes sense to optimize to Actions Per Visit (APV), or Actions Per Daily Unique visitor (APDU). But if you are spending serious time and money then you need to track these costs and what they generate.

Lights! Camera! Actions!

Before this kind of thing makes any sense at all you have to define and start measuring the on the kinds of action you are trying to get visitors to take. Are you selling things? Are you getting paid for advertising shown on your site? Are you trying to develop leads for your business? Are you trying to get people to download something? Are you trying to get people to register or sign up? Whatever actions you want people to take on your site, they need to be measured if they are going to be the basis for your ECPA (or APV, APDU). Most of these things can be measured using Google Analytics.

In any case, once you have tagged or otherwise instrumented your site to capture your desired actions, then you can track ECPA (or APV, APDU) associated with your site.

Then when you make big changes, you can see whether they improved your site’s performance. You can measure the effectiveness of your SEM, your CPC campaigns on search engines, your affiliate programs, and your efforts to publicize your site.

Measuring Dollars Out per Dollar In

ECPA is a pretty good measure, but, it only measures efficiency on the cost side. You also want to measure the return you get in dollars and cents. You can do this (or approximate this) if you can come up with a dollar value for each of your site’s target actions, either using an average value per action type or actual value per action, then you don’t need the oversimplification that focusing only on ECPA imposes. Simply put, all actions on your site are not worth the same amount and it actually makes sense to spend more on actions that are worth more. What you really ultimately want is an ROI. I’ll talk about that in a later post.

Tags: Conversion optimization, Cost per Action, CPA, eCPA, Optimization

Math Marketing: Excellent White Paper by Dimitri Maex

Mar 15, 2010 Industry News, Marketing And Advertising Analytics, Optimization, Statistics, Web Analytics

Dimitri Maex is the Managing Director Marketing Effectiveness at Ogilvy & Mather, and the author of a fantastic white paper that is posted HERE on the WPP website . What is so great about it is that it presents exactly what most companies need to know in order to get started in harnessing the full power of quantitative marketing methods, in a package that only takes about 15 minutes to read.

He starts with the history of quantitative marketing, gives a sense of the place of “math marketing” in the current business landscape, describes the types vendors with which a company can ally, and the wraps up with how a company should organize and hire to around the new skills and challenges peculiar to the coming era of quantitatively-driven marketing.

Some nits:

I don’t like the sound of the name “math marketing”. It’s just that the math doesn’t do any marketing – people still make the decisions and integrate the insights into their work, they just use data-based metrics and statistical techniques to assist them in getting a coherent picture of what is working and what isn’t, and formulating what might work in the future. It is probably also a terrible way to brand something you are selling to execs who mostly sucked at and avoided math in school. It’s like calling it “eat your vegetables marketing”.

The section on vendors is far from exhaustive. He leaves out SEM/SEO agencies in particular, and provides only the massive brand names in most of the categories he is describing. I guess Maex works for an ad agency – so he’s not responsible for selling you on his competition – but I’d look elsewhere for a buyer’s guide.

Whatever, he is right on the money about the current state of affairs and where most companies need to go.

He wraps with a couple of lists: Seven Steps to Increased Accountability, and Seven Steps to Increased Accountability to Transformational Consumer Insights.

This is a great document for business folk who want to understand the big picture of marketing analytics and quantitative marketing techniques, and want to understand how to manage them to best effect.

Tags: Data Mining, Dimitri Maex, Doubleclick, econometric models, Google Trends, Marketing Analytics, marketing mix models, Math Marketing, Microsoft, Ogilvy & Mather, quantitative marketing